history of the wheeling machine

Also known as "English Wheels"

A brief history

Sheet metal was traditionally the original craft

of a blacksmith, hammering metals to make armor,

"beating" them out of flat sheet metal over

anvils, shot or sand bags or using hollowed-out

wooden forms as patterns. The recognition of the

panel beating trade occurred circa 1900 due

mainly to the developing automotive industry.

Body building involved a great deal of intensive

work, because each body part had to be very

smooth, the industry developed, the trade became

highly skilled, organized, and respected

worldwide.

As the automotive and aviation industries grew

larger, mainly due to the war around that time,

requirement for quality increased as did the

need to form large panels free of hammer marks

and the stresses produced from hammering the

material. From this necessity the English wheel

was born.

The exact date of the first machine isn't known,

but it is thought that the concept was first

produced in France in medieval times, where

possibly a wooden frame was utilized.

Commercial production is thought likely to be

around 1890 possibly produced by large foundries

in the midlands, which is still to this day the

heart of sheet metal craft.

At that time there were a few large engineering

companies with sufficient knowledge and

industrial expertise to produce the vast

castings required. Edwards was one such firm,

marketing the equipment from their London

premises. Kendrick, and Ranalah where also well

known manufacturers from around 1900 onwards,

producing machines with throat sizes of up to 48

inches (120cm), primarily aimed at the aviation

industry.

Most of those early machines still remain in use

to this day. These are widely respected machines

that command high prices when they are offered

on the market, although they rarely come up for

sale. For example, a 42 inch machine in working

order is likely to achieve upwards of £6,000

and, if you’re lucky, you might get the matching

anvils, although these would have been well

worked and have become extraordinarily hard due

to them becoming “work-hardened” over the years,

much like a railway track ages over time.

Some of these machines are nearing a century old

obviously wear out, but as with most good

quality engineering, these machines can be

brought back to life by replacing worn or

missing parts, as the components tend to be

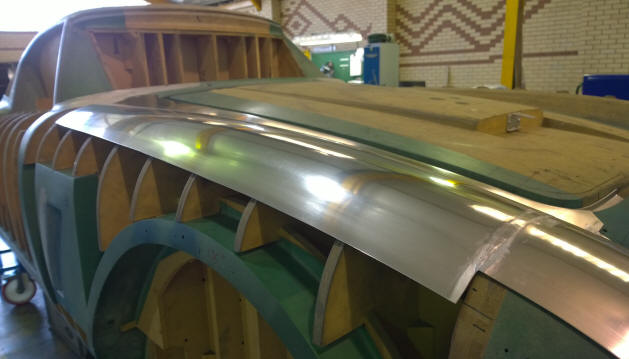

fairly simple to reproduce. “Hollowing” of the

top anvil is a common problem and the anvil can

be re-cut or re surfaced, Original pattern lower

anvils, are CNC cut in hard machine steel. The

replacement parts made to much finer tolerances,

and almost zero run out on the anvils.

Slop or play in the lower adjuster is common

too, sometimes rectified by simply heating the

original leaded mount with a gas torch or blow

lamp, melting it back into shape and place.

More recent products have used different methods

of manufacture to produce the C section frame,

such as sheet metal, or rolled hollow section

tubing (RHS) with varying levels of success,

these are mostly mass produced in China, but the

principle remains the same.

.jpg)

In 2006 Justin Baker was asked by a friend to

help him source an English Wheel. After several

months of searching he was finding only the old

machines mentioned above which were commanding

very high prices.

Justin decided to put his design and engineering

skills to good use and with the use of a

computer aided design and manufacture. After

much research he began designing English wheels

and having them made to his own specification

using the local small manufacturing firms.

Several types were developed and produced over

the following years, including sheet metal

designs such as the Raptor-2000 that is now

being re developed and marketed by

Clement & Bogis

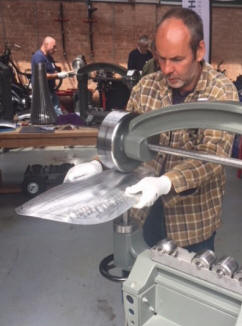

Below, a great fun weekend where the machines were demonstrated at Race-Retro, where people could come and try for themselves, we met some famous faces that weekend too.

In 2008 patterns were made for the very first

cast machine, which is now manufactured in small

quantities in his home town in Northamptonshire,

England, from where they are dispatched

worldwide to be put to work.